The fundamental difference between the Protestant’s cross and the Catholic’s crucifix lies in the Protestant belief that Christ is no longer on the cross. He has resurrected and ascended.

Or so Protestant polemics go.

In what follows, I do not care to discuss Catholic vs. Protestant soteriology or the differences between their accounts of the death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. All I wish to discuss is the fact that, a few years ago, this here Protestant found immeasurable comfort in Christ on the cross – a crucifix on the wall in a Catholic nursing home chapel.

I’d been in and out of the nursing home visiting my 51-year-old mom in the last days of her fight with cancer. None of us expected the illness to progress as quickly as it did. But in a mere month and a half, we went from optimism about her diagnosis to staring down her mortality and releasing her into the loving hands of Jesus.

My encounter with the crucifix began on the night I had to decide to sign my mom up for hospice care. She was so weak I had to help her hold the pen. Even then she could only make a scratch on the page. Her once-beautiful signature which used to sign my birthday cards, report cards, and detention slips was reduced to a single scratch on several pieces of hospice paperwork.

In this moment I was forced to grapple with the existential angst, fear, and brokenness that smothers ever-shattered souls stepping one inch closer to the inevitable realization of our mortality.

Mortality.

Mom is mortal.

I am mortal.

I needed to leave the room as soon as we signed all the forms. I didn’t know where I was going. I found myself in a wing of the nursing home I hadn’t visited before, looking for some privacy.

Barely holding back tears, I stumbled into the chapel.

Now, despite the fact that I’m a Christian – not to mention a pastor – I did not choose the chapel for some spiritual reason. I simply chose it because no one would be able to find me in there. Or more specifically, no one would be able to hear me weeping in there.

I looked around for a second or two, not noticing anything about the chapel except the fact that the least visible place in the room was on the floor behind the back few pews. It was the perfect place to hide. It was a perfectly private place to grieve.

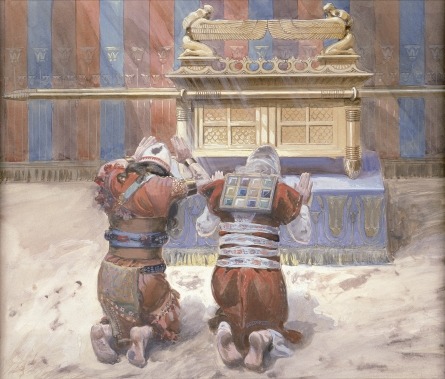

I don’t know how long I sat there with my face in my knees. Fifteen minutes. Thirty minutes. An hour. I don’t know. But after a while, I looked around the room and saw a plethora of Catholic images and icons, most of which are probably quite familiar to Catholic Christians but are quite foreign to us Protestants, who sanctimoniously brag of our lack of “graven images” and our risen Christ.

It was clear in these various items that the crucifixion of Jesus and the sufferings of Mary are of foremost importance in the hearts of the persons who designed this chapel. From the seven depictions of Christ’s crucifixion story to the mother of Jesus holding her infant son as she stretched out her arms to the weeping worshiper, the entire chapel was an invitation to see our sufferings – our very humanity – in light of the fact that neither Jesus nor Mary was exempt from suffering, pain, or death.

In fact, the truth experienced in that chapel was not merely that Jesus was not exempt from suffering or death, but more specifically, that Jesus shares in our suffering and death and we share in his.

On the opposite wall from the statue of the virgin and her baby boy hung a wooden crucifix. Not a pretty one. Not a bloodless one. A horrific one. A crucifix agonizing to see, even though its monochromatic varnish shields viewers from all the viciousness of the reality it depicts. In this crucifix, I saw that with every broken rib and visible wound, our God hung naked before the world, taking upon himself, not only all of our sin but all of our suffering. This is a God who did not remain indifferent to our suffering, our illnesses, our cancers, but who on that cross waged war against our mortality.

This is a God whose resurrection was preceded by a deep and unrelenting experience of our mortality. Before he ever won the war, he first lost this battle to death.

Could it be that Catholics “leave Christ on the cross,” not because they fail to recognize his resurrection, but because they believe the God who lost his Son on the cross suffers with me as I hide on the floor of this chapel? Maybe God is not just up in the sky somewhere looking down half-callously saying, “Hey, don’t worry about how bad it hurts now. She’s going to heaven because Jesus died for her sins.” He’s not up there saying, “Here, have this opiate and buck up.” Instead, in the crucified Jesus, God draws near to us, weeps with us, feels forsaken with us, knows loss with us, and even dies with us. Even his mother shudders from the pain of it.

Mortality.

Mortality.

Mom is mortal.

I am mortal.

Jesus was mortal.

Jesus died.

God was dead.

And while I know that the story does not end there, while I know Jesus came down off that cross and ascended as the Lord of Life, there is a deep and infinite beauty in knowing that my mother’s broken body is preceded by the broken body of her Creator.

An empty cross certainly announces victory over death. But a crucifix, hoisting the dying Savior with outstretched arms, is a warm welcome to all who are wrecked and weary.

Resurrection is coming.

But for now, we suffer. Together.